Arequipa or: That Time I Found a Good Coffee

Expectations play a major role in determining overall enjoyment of a place. Sure, some locations (like Torres Del Paine) are almost always viewed in a positive light, but most destinations will see visitors have widely different opinions depending on their expectations beforehand and external factors (e.g. mood, weather, accommodation, travel fatigue or encountering crime) while there.

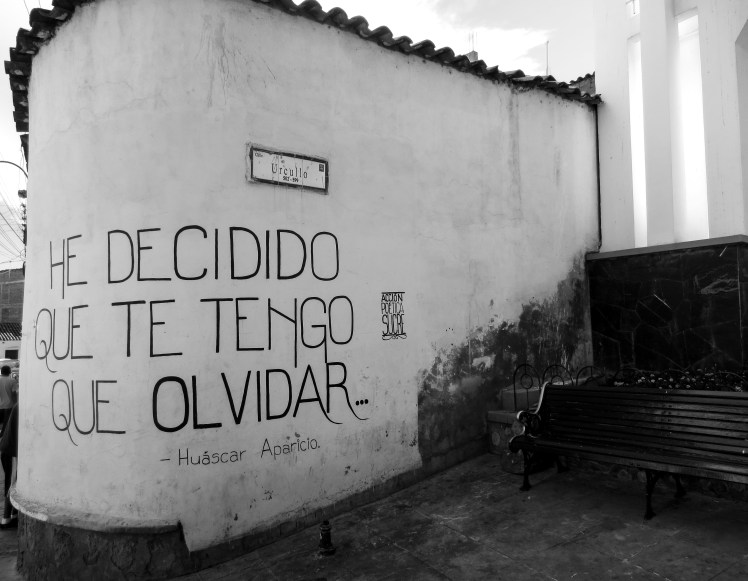

We hadn’t heard a great deal about Arequipa before arriving, and perhaps having no expectations was why I enjoyed it so much. All I knew was that it had a picturesque town centre and was close to a few volcanoes. This was definitely true, and the volcanoes were much closer and more imposing over the city than I had imagined. We arrived at 4.30am after an overnight bus from La Paz, and once we reached the centre I was struck but how clean the cobbled streets and colonial buildings were. We sat in the main square as the sun rose and watched the city slowly wake up. There were a lot of agencies trying to sell Colca Canyon (the second deepest canyon in the world) tours in the Plaza de Armas which could be a little annoying, but it was contained to this area and they didn’t keep hassling after we politely said no.

We chose to see Colca Canyon without a tour, which was easily organised and a bit cheaper. The bus we took stopped at the Condor lookout for about 40 minutes and we saw many of these enormous birds from close range. Whilst staying in Cabanaconde we felt four earthquakes, which was a strange experience and a reminder of how active the west coast of the Americas is. When we returned to Arequipa Andrew climbed Volcan Misti, the closest and in my opinion the most impressive looking of the three volcanos that border the city.

It is no secret that I enjoy food. And coffee. A lot. We reached Arequipa after almost two months in Bolivia, a country not known for its culinary delights. Fried chicken and hot chips dominate most local restaurant menus and street food stalls. Coffee options are either instant, or very weak half froth cappuccino. Whilst this all continued into Peru, the food scene in Arequipa was much more varied. It was also very cheap. I found an excellent café/chocolate shop called Chaqchao that I visited every day and we also did a chocolate making workshop there. It felt like we’d accidentally returned to Australia – they had pallet furniture and I ate a poached egg with avo! The chef who ran the workshop introduced us to cacao tea – tea made from cacao shells that are usually discarded in the chocolate making process. I am convinced that this might be able to cure my after dinner chocolate addiction and am hoping I can send some home or get some back in Australia.

I was torn, almost feeling guilty, by enjoying Arequipa so much. One reason for travelling through South America for such a long time was to experience completely different cultures. And here I was getting really excited about Australian style coffee and food. These kind of luxuries are not necessary to be happy in life, as we saw countless times throughout Bolivia. Nevertheless, it was nice to indulge in some home comforts for a few days.

Erin

You must be logged in to post a comment.